Summiting Mt. Rainier

I climbed Mt. Rainier a couple weekends ago. The summit was a new high point for me, 14,411 ft. It ended up being one of the most fantastic – and difficult – adventures I’ve had. What a beautiful mountain.

It started Thursday evening when my rope team met up to do a gear check and talk about plans, goals, and logistics for the trip. I had borrowed a lot of gear, and it turns out I’ve never been mountaineering before. I hike and rock climb, so I have some basics like a harness and helmet, but glacier travel was totally new to me. A friend lent me an ice axe, glacier glasses, extra carabiners, collapsible shovel, an avalanche beacon (despite low avalache risk for the weekend), cramp-ons, double plastic mountaineering boots, and a balaclava (full head and face mask) in case of extreme cold at the top. I ended up using everything except the beacon and balaclava. This trip was wild.

We confirmed that everyone was fully equipped, had a couple big bowls of pasta, and enjoyed a beer over discussion. It was really good to talk about goals for the trip, summer camp style. Mine started out as pretty much just wanting to reach the summit, but I started to realize there was going to also be a huge opportunity for learning and practice over the weekend, and I started getting more excited about that. The phrase “mental elevation” came up, which I thought was cool but wouldn’t really understand until about 60 hours later.

Satisfied with our discussion and bags packed up, we set our alarms for 4:45 am and got in sleeping bags to catch as much sleep in the remaining 5 hours as possible.

And 4:45 came quickly, as it always has in my experience. We secured our packs, loaded up the car, and took off for the mountain, about 2 hours southeast of Seattle. We had reserved campsites ahead of time, but still ended up getting caught in a line at the ranger station for about 45 minutes. You don’t expect a line at 6:30 am, but that is how the mountain works. We filled out our trip plan and set out. We ended up with a campsite at Glacier Basin for Friday night (about 3.5 miles in at 5,000 ft), Camp Schurman for Saturday night (another ~3.5 miles at 9,500 ft), and another night at Schurman on Sunday if necessary. We wouldn’t be doing the rush up and down the mountain that some people do, so there would be time to practice glacier skills and get a bit used to the altitude. Pretty much ideal.

So we strapped on our packs and got moving. I think we were all hauling about 40-50 lbs, but even so, 3.5 miles goes quickly. The trail was nicely maintained and mostly snow free. They had had a serious wash out a few years back, and the trail has been completely rebuilt. All in all, an easy walk. We got to our first campsite around 11 am, leaving plenty of time to practice knots and self arrests. We set up camp and took a breather. The 4:45 am wake was pretty apparent, and our conversational skills were in a serious decline. I looked over a mountaineering book and dozed off on a sunny rock.

After a bit of back and forth between half-wakeful studying and half-restful dozing, we all got back together for the hands-on practice. We roped up, did some laps around the snowfield, practicing commands and arrests. Informative and necessary, but definitely clouded by lingering exhaustion. Around 5 or 6 we decided to cook some dinner and get tidied up for sleep. The plan was to hit the trial while the snow/ice was still good (i.e., not slushy yet), so we set our clocks for a 4 am wake up. We were in our bags by 10 pm, and these 6 hours would be the longest rest of the trip.

And this time I was a little bit more ready for 4 am when the alarms started chiming. It is a good feeling to be up before the sun. The moon and stars were beautiful. We had a quick breakfast and chai tea and packed up camp. By the time we got moving, the sun was starting to shine on the western edge of the basin. It felt good to be moving in the shade – things would clearly be getting hot when the sun surfaced fully. We worked our way slowly up Inter Glacier on the way to camp Schurman. There weren’t any crevasses on this one, but it did get pretty steep toward the end. Our early start paid off, and we were rewarded with some pretty spectacular views by about 9 am. At the top of the ridge we roped up to move onto Emmons Glacier. We were expecting minor crevasses, but mostly we wanted to get some experience on the rope and with our knots. We snacked and hiked, practiced setting some gear, snacked and hiked some more. We might have taken our time a little too liberally and ended up at camp around 1 pm. We were greeted by David Gottlieb, a reknowned mountaineer who has climbed Rainier enough times to be “too embarassed to keep track” anymore. He gave us some tips on our knots and packing and wished us luck. We were reassured to find out that he would be summitting Sunday morning about the same time as us.

1 pm may not seem like a late arrival into camp, but we were already moving pretty slowly. At 10,000 ft everything takes longer than you expect. We set up the tents, got a water-drip going to fill our bottles, played a game of Euchre, and suddenly it was 5 pm – later than we had hoped for dinner. We cooked, ate ravenously, and cleaned. Suddenly 8:30 pm. We decided on a very early start – 12:30 am. So we set our alarms for 11:30 pm and got in our bags for a glorious 2.5 hours of rest.

I actually didn’t realize that we had planned on so little rest (or I didn’t know what time it was when we went to sleep), and I felt surprisingly good when the clocks went off. Adrenaline and excitement for the summit certainly had something to do with it. It was beautiful out. The snow and ice were nice and solid, the sky was clear and full of stars. The moon was just rising and the whiteness of the mountain made the landscape feel extraterrestrial. Again, altitude and lack of sleep contributed. Either way, really amazing. We roped up and got in line. There were already other teams leaving, and we ended up being about the 7th team to set off. More would be coming up behind us, and it would clearly be a busy day on the mountain.

Things got steep right off the bat, but we were in a pretty good zone. Circles of light from headlamps were moving up the glacier ahead of us and behind and it was easy to fall into a rhythm. After trekking a good way up the first section we stopped for snacks and realized it was already 2:45 am. There was one tricky section involving a snow bridge that had lost some of its integrity the day before, but it was still cold enough that there were no issues moving across it. We pressed on and it was 4:30. The sun was starting to rise directly opposite the glacier, giving us a wonderful light show. It got bright and things warmed up a bit, with the wind picking up as well to counteract the heat.

This continued for some time. We had some trouble with the pace and congestion at this point – we kept having to stop behind slow groups, but couldn’t get enough momentum to pass them and stay ahead. So we alternated between getting cold and getting tired, not ideal. Around 7:30 am we stopped for a longer break, about 15 minutes. We were about 700 ft from the summit, but we were getting worn down. The altitude was kicking in and it was hard to stay focused. We chatted about our energy level and motivation, and decided that if we weren’t on the summit by 10 am we would turn around and head back. Pretty generous, but it seemed like a good goal at the time. We had another snack and got our legs moving again.

The slightly longer rest and chat had motivated us, and we ended up being pretty solid the rest of the way to the summit. We slowly realized we had arrived as we saw rock and climbers resting. 8:30 am. There were some wispy clouds around and the wind was whipping across the crater. Not a very hospitable place. We could see north to Baker, but a light haze kept the views from extending more than a couple hundred miles. It felt really good to be at the top, and a huge relief to know that we wouldn’t have to go up any further.

The wind was keeping us from enjoying the rest too much though. We were feeling the cold and decided it would be best to make our stay short. We snapped a few photos, tightened up our gear and set off for the descent. We kept our cramp-ons on in case we came to any icy patches, but things were getting pretty slushy and we probably could have moved a bit faster without them. Still, the descent was a relief and it felt like we were covering ground in no time. We stopped briefly a couple more times to snack and plodded on. We found that the snow bridge we had crossed earlier had melted out a bit more, requiring a short jump to get across. We played is safe and set some protection in the snow in case of a slip and made it across without trouble.

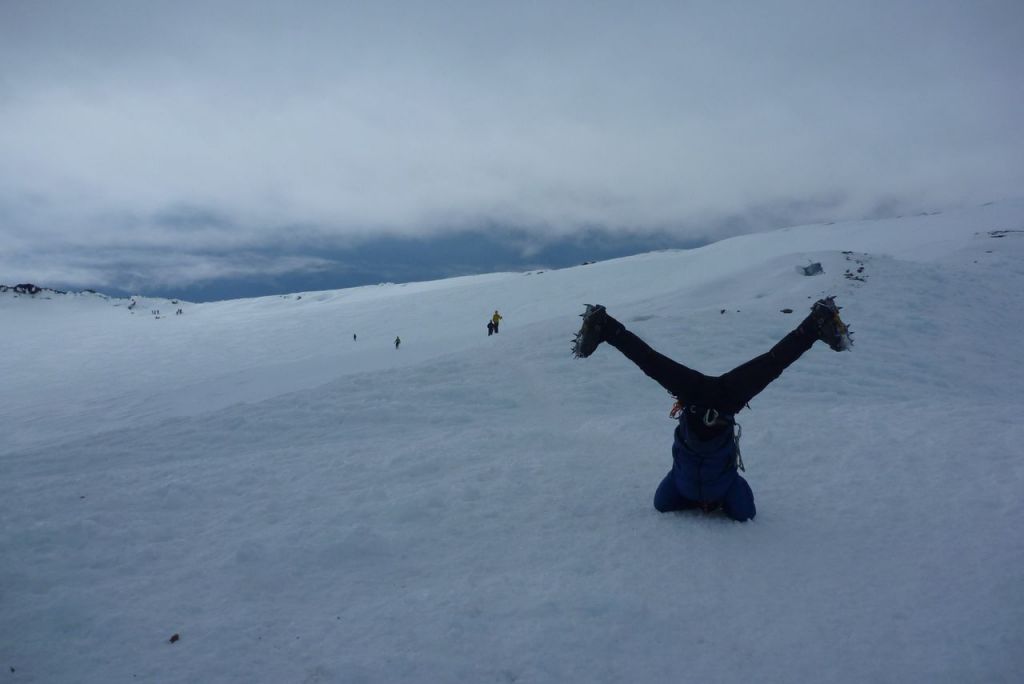

After some final knee-high-slush trudging, we made it back to Camp Schurman where are tents were waiting for us, 1 pm. We shed our packs and crawled into sleeping bags for a quick rest. We could stay another night there if we wanted, but we had heard that there were thunder storms were on the way. We slept about an hour and a half and packed up camp. We loaded up our bags by 5 pm and got on the rope for one last stretch of glacier travel. We were exhausted but happy, and everything went smoothly. We got to Inter Glacier, the steep snowfield from the second day, and were greeted by a nicely groomed glissade track. Strapping our gear on tightly, we sat on our butts and got ready to slide. It felt terrific. The 3-mile snowfield which had taken us 3-4 hours to climb a day early quickly receeded in about 15 minutes of amusement park-style enjoyment. The snow cooled our legs, pretty much bliss. Within the hour we were back to our first camp and on our way out on a 3.5 mile dirt trail. Our heads were clear with the reduced altitude, but foggy from exhaustion. The hike felt more like about 7 miles, but we made it. We got to the car at 9 pm and took our boots off to great relief. Success! We had reached the summit and made it back down in one piece. It felt incredible. And it was really hard. We were totally beat, loopy, hungry for something other than Power Bars.

We got in the car hoping to find burgers, but Enumclaw is a sleepy town at 10 pm on a Sunday, so we settled for the 24-hour Safeway. Another meal of snacks, but at this point it didn’t really matter. We got back to Seattle around midnight, ready for some hot showers and warm beds. In bed by 1 am, up at 8 am for work. 7 hours felt luxurious. What a weekend.