Rock Climbing on the Right Side of the Brain

What do rock climbing and drawing have in common? I’ve been spending a good amount of time doing each recently, and I’ve found that they are more similar than I would have guessed.

I’ve done a lot of drawing over the course of my life and filled up a number of sketch books in the process. In the past couple years, though, I’ve shifted more of my creative energy to painting, and drawing has fallen by the wayside. To get back into it, a friend recommended to me Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. I’ve started working my way through the book, following the exercises on contour and shape. It turns out I’ve done most of these exercises at some point previously, but I’ve never been consciously aware of the shift to right-brain mode that goes with them.

As for rock climbing, I’ve dabbled for about eight years, but I started getting serious about it three and a half years ago. It has worked out that I’ve had the most free time (between jobs, unemployment) during the winters, which has made me very familiar with the rock climbing gym. I’ve had a number of plateaus in my climbing ability, but I’ve put it some solid effort and training this winter and have progressed to a fairly advanced level.

So what’s the deal, how are the physicality of rock climbing and the creativity of drawing connected?

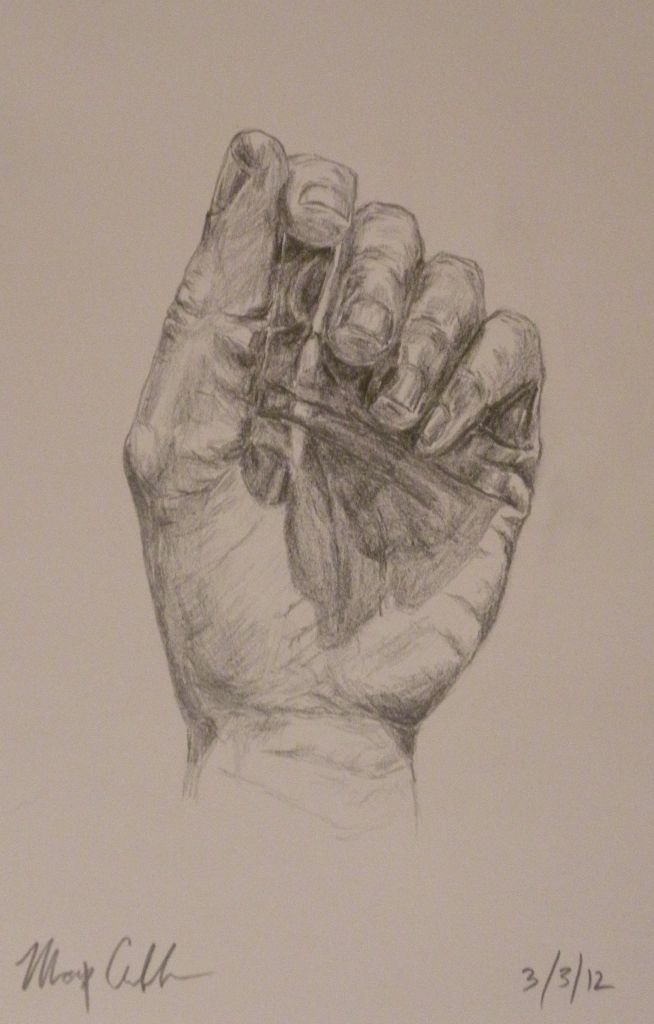

In essence, they are different ways of interacting with the same things: space, dimensionality, and texture. In drawing, you use your eye to follow an object, to perceive the way light reflects off the grooves, indentations, bulges, and flats. In rock climbing, you use your hands and body to do the same thing. You perceive the physical properties of the rock through your sense of touch. In both endeavors, it took me quite a while to realize the importance of utilizing this perception.

Rock climbing is very difficult as a beginner. It engages a whole new set of muscles, so even someone who has gotten incredibly strong through weight lifting will probably have a lot of trouble (and there’s something cathartic about watching beefy guys struggle to get up a wall). You spend a long time grasping for something to hold on to before building up the finger and core strength and awareness to move through routes smoothly.

As the fingers strengthen, though, one gains awareness of subtleties in the body and the rock. I especially notice this in the climbing gym where the same hand holds get reused over and over again. As I improve (over months, to give a sense of scale), my sensation of a particular hold changes. This evolution happens slowly, maybe I find there is a certain angle and finger position that feels a little bit more stable than I remember. A groove feels slightly deeper, a ridge sharper. At some point, holds which I couldn’t imagine clinging to before are suddenly accessible, even easy to hold on to.

New awareness in the fingers leads to new awareness of the whole. The space between the hand holds becomes more concrete. With additional core strength, the body can navigate this space smoothly and efficiently. This becomes ingrained in the body’s movement; the brain quiets and lets the perception of shape take over.

This may be beginning to sound a little bit more like drawing. Although I’ve been engaging in a shift to my right-brain while doing art for years, I wasn’t conscious of what that really meant until I started working through Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. The main focus of the book is teaching the reader to see. Not just to recognize an image or object as something it already knows, but to explore the edges with the eye, see the negative shapes between objects, experience the subject as it really is. It turns out the right side of the brain is really good at this, and the left side of the brain is really bad at it. Unfortunately, the left side usually wins out for our attention and suppresses this deep right-brain perception with logic and symbols.

Now that I have an idea of what to look for, I’ve noticed some changes that occur when I’m able to reach that right-brain mode. The most obvious shift is to extreme focus. Time drops away, external stimuli become difficult to process, distractions lose their appeal. I am able to look closely and carefully, and to slowly trace an object with my eye. My hands are well trained enough to respond to this perception by copying it. I can quickly tell if there is a discrepancy between the object and my interpretation of it and make an appropriate change. The deeper into the zone I get, the clearer the textures, contours and shapes become, and the easier they are to translate onto the page. It is a blissful feeling of awareness.

I’ve improved my level of perception of shape through sight and touch, and I am curious how perception through the other senses evolves when well trained. I imagine there must be corollaries for smell, taste, and hearing. Although I’ve played music my whole life, I can’t say that I feel a deep connection to hearing. Perhaps the creation of sound is distinct in the brain from the perception? I’ll have to look into that. I think my music could use a good dose of right-brain focus.